The Revolutionary Soldier, Sailor, and Patriot of Orleans

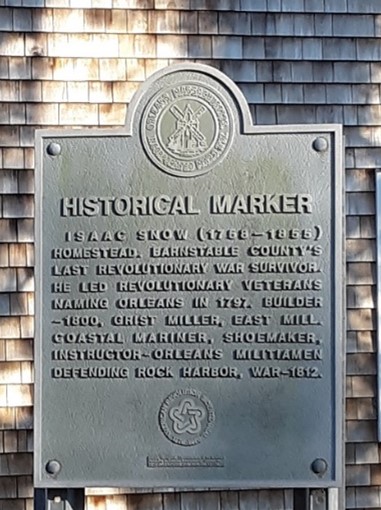

Isaac Snow’s participation in the American Revolution is a remarkable and iconic story that took place on Cape Cod, in Boston and Newport, at sea on several American privateer vessels, in Portugal, France, and England. When he returned home near the end of the war, he began a second life as a contributor to the

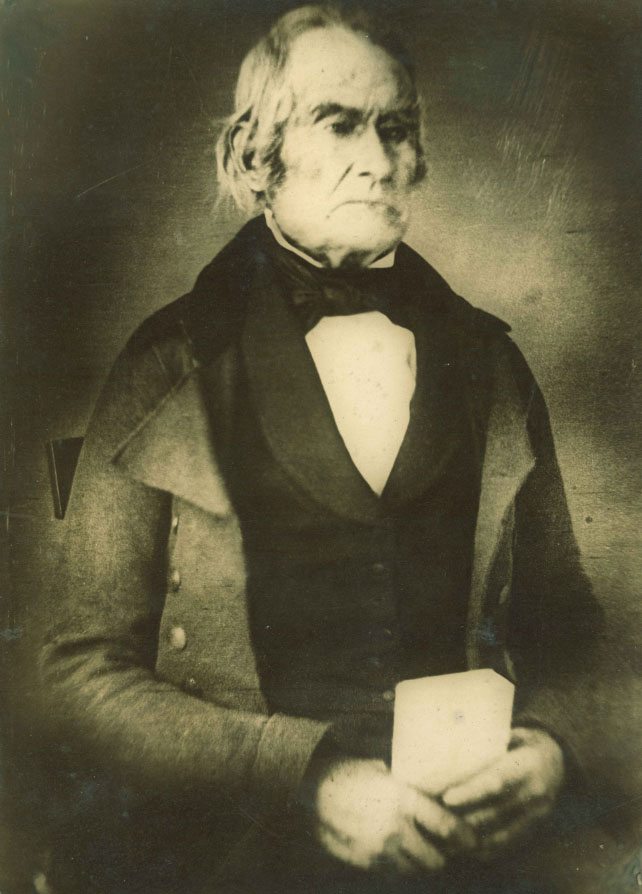

Isaac Snow at 94

establishment of the Town of Orleans and as a significant participant in the growth and development of the new town. He lived to the age of 97. When he died in 1855, he was the oldest Revolutionary War veteran in Barnstable County, and one of the oldest in the nation. He is one of the very few to have lived long enough to be photographed.

Isaac was born on 18 December, 1758 in the South Parish of Eastham on Cape Cod. This was the land that became the Town of Orleans in 1797. His parents, Elnathan and Phebe Snow were descended from the first British colonists to settle on the land that was to become Eastham and then Orleans. In 1644, Nicholas Snow and his wife Constance Hopkins Snow, a Mayflower passenger, were among the first seven families from Plymouth to settle in what was then called Nauset. The Snows were assigned the southernmost tract of land in Nauset, a section called Namskaket. Thus, Isaac had deep roots in the history of Nauset, and was about to make his own contributions to the family’s heritage.

The house where Isaac was born still stands today on Brick Hill Road in Orleans. Little information on his childhood is available, but that changed in early 1776. As he entered his late teens, the Revolution was heating up. Following the events at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill in 1775, General Washington sought to double the size of his army surrounding Boston and called for 200 men from Barnstable County. Bounties of 8 pounds per man were offered. In addition, the Eastham Town meeting voted to give their representative instructions to urge the Continental Congress to “declare the united colonies independent of Great Britain.”1

In early February of 1776, a recruiting sergeant from the Continental Army visited Eastham, and seventeen-year-old Isaac Snow overcame the objections of his family and enlisted. Being somewhat short in stature, Isaac related “When measured to see if I was tall enough to answer the law, I stretched myself up all that was possible, and then was but just able to pass.”2 He was issued a firelock, bullet pouch, powder horn, cartridges, a bayonet, and a hatchet, and set off with thirty-nine other recruits for Boston under Captain Solomon Higgins, also of Eastham. The company arrived at Roxbury to join other units of the Continental Army that had surrounded Boston.

In March of 1776, General Washington decided to build breastworks on Dorchester Heights to strengthen the

Birthplace of Isaac Snow as it looks todayAmerican position. Isaac and his company joined the work after being issued spades, crowbars, shovels, and picks. He reported that the work party consisted of 1200 men, with an 800-man covering party. The works that were built at Dorchester Heights and the failure of the British to destroy them by cannon fire were instrumental in encouraging the British to evacuate Boston on 17 March. Isaac and his company were among the Continental force that marched into Boston much to the joy and relief of the remaining inhabitants. About 1500 loyalists, or Tories, vacated Boston with the British forces.

When his three-month enlistment was up, Isaac returned home “strongly in love with my country’s cause, so much so that I soon enlisted again for nine months in a company from Eastham under Capt. Isaiah Higgins, and again went to Boston, and was employed some time building fortifications in Boston Harbor.”3

When that enlistment expired, Isaac enlisted again enrolled for another six months in a company led by Captain Hamilton of Chatham. That company marched to Rhode Island and was involved in building fortifications and military drills.

After his third army enlistment expired, Isaac turned his attention to the sea. At the time of the Revolution, Britain possessed an enormous advantage controlling the oceans, sporting the most powerful navy in the world. While historical attention is often focused on the emerging Continental Navy, much of the American success at sea was due to the privateers that were authorized by the Continental Congress on 23 March, 1776. Privateers were privately owned vessels which were outfitted for war and issued Letters of Marque, which authorized them to challenge and seize enemy vessels to disrupt British shipping. All this was done under regulated conditions, with lightly armed commercial ships being the ideal targets. Records show that about 1700 Letters of Marque were issued to about 800 private ships, which resulted in the capture or destruction of about 600 British vessels.4

In January of 1778, Isaac signed on to the ship Defence which had been outfitted with 18 guns and was under the command of Captain Samuel Smedley. After three days at sea, smallpox broke out on the ship spreading sickness among the crew. While this was occurring, a British ship was sighted, and Captain Smedley decided to engage, even though a number of the crew were sick. Isaac reported that he “could sit up and walk some, so I took a gun and sat upon the hencoop till the action commenced, when I forgot my sickness, sprang to my feet, and loaded and fired my piece as fast as possible.”5 After a battle of one- and one-half hours, the British ship struck her colors, a prize crew from the Defence was put on board, and the prize was taken to Boston.

Isaac then signed on to another privateer ship under Captain Stephen White of Salem. While at sea, a British Navy frigate bore down on White’s ship was captured. Isaac was taken to Lisbon, Portugal and put on a prison ship in the harbor. Captured privateers would be held for the duration of the war or until exchanged. Along with several of his crew, Isaac managed to escape, and encountered a Mr. Baptiste, who he identified as a Frenchman employed by America to look after my countrymen”.6 Through Mr. Baptiste, Isaac learned of a French fleet in Brest, France that was to sail to America to aid the revolution. Isaac made his way across Portugal, Spain, and France to Brest where he found a large fleet consisting of one frigate, one sloop of war, eight line of battle ships, and forty transports carrying 10,000 troops under Lafayette. The fleet was under the command of the Count d’Estaing. The fleet landed at Newport, Rhode Island and put ashore the forces that would be so vital to the American cause. Once again, Isaac trekked home to Eastham on foot.

Once home, Isaac spent some time with his family, but was apparently not convinced his role in the Revolution was over. After three army enlistments and two harrowing stints at sea, he signed on with Captain Sears for yet another privateering voyage on a brig mounting ten guns. After being out nine days, the brig was captured by a British frigate. The crew was taken to England where they were condemned to the notorious Mill Prison by the Admiralty Court for “treason and piracy upon his majesty’s high seas.”7 While imprisoned, Isaac engaged in several unsuccessful escape attempts. He also participated in an informal “prison school” where prisoners with knowledge in various topics instructed those willing to learn. He served twenty-two months at Mill Prison, and was released in a prisoner exchange.

Isaac returned home in 1784 and married Hannah Freeman on March 16, 1786 and fathered nine children. He took up the trade of shoemaking which he very possibly learned while confined in Mill Prison. In 1880, he was a builder and became a one-fifth owner of the East grist mill in Orleans located on high ground off of Great Oak Road. The other owners were William Knowles, Samuel Smith, Edward Jarvis, and John Freeman. Isaac also served as the miller. In 1967, the mill was dismantled, moved to Sandwich, and reassembled on the grounds of the Heritage Museum and

Old East Mill, Orleans

Gardens where it stands today. In 1828, he returned to shoemaking, until retiring on his veteran’s pension.

In 1797, the Town of Orleans was established as an incorporated municipality, separating from the Town of Eastham. During the incorporation process, Isaac was appointed to a committee charged with naming the new town. At the time, pro-French sentiment was very high as a result of their assistance and support during the Revolution. It is probable that while Isaac was in France awaiting passage home, he became aware of the

wildly popular Louis Phillipe Joseph, the Duke of Orleans. The duke was a wildly popular friend of the common man, and participant in the French Revolution. He was ultimately executed during the Reign of Terror. The preponderance of evidence strongly suggests that Isaac was a driving force to make Orleans the only town on Cape Cod to have a French name.

During the War of 1812, Isaac served as an instructor to the Orleans Militia, who repelled the British attack on Rock Harbor in December of 1814. He died on 12 March, 1855 and is buried in Orleans Cemetery.

Grave of Isaac Snow, Orleans Cemetery

Historical Marker at Snow Birthplace

Author: Ron Petersen

1 Pratt, p78.

2 Snowden, p4.

3 Myrick, p6.

4 Frayler, p1.

5 Myrick p6.

6 Myrick, p8.

7 Myrick p.10

Bibliography

Barnard, Ruth L. A History of Early Orleans, Taunton, Massachusetts, William S. Sullwold Publishing, 1975.

Dolin, Eric Jay, Rebels at Sea: Privateering in the American Revolution, New York, Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2022

Frayler, John, “Privateers in the American Revolution, A Means to and End”, National Park Service Website.

Hopkins, Giles E. Now Listen To Me, New York, Unpublished, 1953.

Jalbert, Russel R. Where Sea and History Meet: 4000 Years of Life in Orleans, Orleans Bicentennial Commission, 1997.

Myrick, William P. Mr. Isaac Snow of Orleans: Revolutionary Soldier-Sailor Barnstable, Massachusetts, F.B. Goss Steam Book and Job Printer, 1881.

“A Cape Codder in the Revolution”, Yarmouth Register, March 25, 1916

“Reminisces of a Revolutionary Soldier Now Living on Cape Cod”, Barnstable Patriot, August 16, 1853.

“Snowden” Orleans, Massachusetts, Unpublished

“The Old East Mill” Yarmouth Register, July 17, 1980